Kingdom Of Scotland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kingdom of Scotland was a

In the 16th century, under

In the 16th century, under

The

The

Scots law developed into a distinctive system in the Middle Ages and was reformed and codified in the 16th and 17th centuries. Knowledge of the nature of Scots law before the 11th century is largely speculative,. but it was probably a mixture of legal traditions representing the different cultures inhabiting the land at the time, including

Scots law developed into a distinctive system in the Middle Ages and was reformed and codified in the 16th and 17th centuries. Knowledge of the nature of Scots law before the 11th century is largely speculative,. but it was probably a mixture of legal traditions representing the different cultures inhabiting the land at the time, including  There is some evidence that, during the period of English control over Scotland,

There is some evidence that, during the period of English control over Scotland,

David I is the first Scottish king known to have produced his own coinage. There were soon mints at Edinburgh, Berwick and

David I is the first Scottish king known to have produced his own coinage. There were soon mints at Edinburgh, Berwick and  Early Scottish coins were virtually identical in silver content to English ones, but from onwards their silver content began to depreciate more rapidly than their English counterparts. Between 1300 and 1605, Scottish coins lost silver value at an average of 12 percent every decade, three times higher than the English rate. The Scottish penny became a base metal coin by and virtually disappeared as a separate coin from onwards.. In 1356, an English proclamation banned the lower quality Scottish coins from being circulated in England. After the union of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603, the Pound Scots was reformed to closely match

Early Scottish coins were virtually identical in silver content to English ones, but from onwards their silver content began to depreciate more rapidly than their English counterparts. Between 1300 and 1605, Scottish coins lost silver value at an average of 12 percent every decade, three times higher than the English rate. The Scottish penny became a base metal coin by and virtually disappeared as a separate coin from onwards.. In 1356, an English proclamation banned the lower quality Scottish coins from being circulated in England. After the union of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603, the Pound Scots was reformed to closely match

From the formation of the

From the formation of the

Historical sources, as well as place name evidence, indicate the ways in which the

Historical sources, as well as place name evidence, indicate the ways in which the

In 1635, Charles I authorised a book of canons that made him head of the Church, ordained an unpopular ritual and enforced the use of a new liturgy. When the liturgy emerged in 1637 it was seen as an English-style Prayer Book, resulting in anger and widespread rioting.. Representatives of various sections of Scottish society drew up the

In 1635, Charles I authorised a book of canons that made him head of the Church, ordained an unpopular ritual and enforced the use of a new liturgy. When the liturgy emerged in 1637 it was seen as an English-style Prayer Book, resulting in anger and widespread rioting.. Representatives of various sections of Scottish society drew up the

The humanist concern with widening education was shared by the Protestant reformers, with a desire for a godly people replacing the aim of having educated citizens. In 1560, the '' First Book of Discipline'' set out a plan for a school in every parish, but this proved financially impossible. In the burghs the old schools were maintained, with the song schools and a number of new foundations becoming reformed grammar schools or ordinary parish schools. Schools were supported by a combination of kirk funds, contributions from local heritors or burgh councils and parents that could pay. They were inspected by kirk sessions, who checked for the quality of teaching and doctrinal purity. There were also large number of unregulated "adventure schools", which sometimes fulfilled a local needs and sometimes took pupils away from the official schools. Outside of the established burgh schools, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk. At their best, the curriculum included

The humanist concern with widening education was shared by the Protestant reformers, with a desire for a godly people replacing the aim of having educated citizens. In 1560, the '' First Book of Discipline'' set out a plan for a school in every parish, but this proved financially impossible. In the burghs the old schools were maintained, with the song schools and a number of new foundations becoming reformed grammar schools or ordinary parish schools. Schools were supported by a combination of kirk funds, contributions from local heritors or burgh councils and parents that could pay. They were inspected by kirk sessions, who checked for the quality of teaching and doctrinal purity. There were also large number of unregulated "adventure schools", which sometimes fulfilled a local needs and sometimes took pupils away from the official schools. Outside of the established burgh schools, masters often combined their position with other employment, particularly minor posts within the kirk, such as clerk. At their best, the curriculum included  The widespread belief in the limited intellectual and moral capacity of women, vied with a desire, intensified after the Reformation, for women to take personal moral responsibility, particularly as wives and mothers. In Protestantism this necessitated an ability to learn and understand the

The widespread belief in the limited intellectual and moral capacity of women, vied with a desire, intensified after the Reformation, for women to take personal moral responsibility, particularly as wives and mothers. In Protestantism this necessitated an ability to learn and understand the

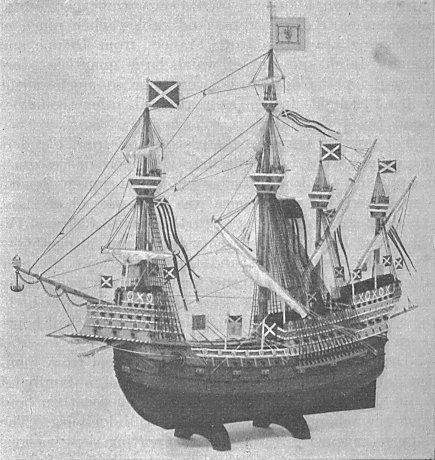

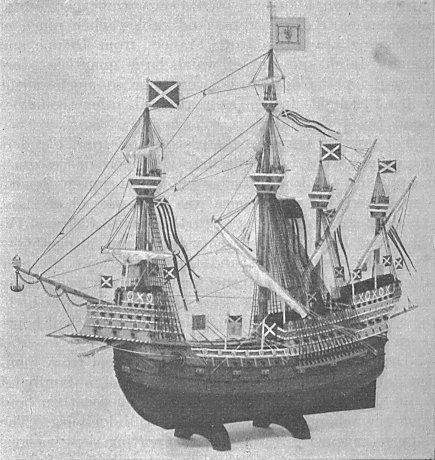

There were various attempts to create royal naval forces in the 15th century. James IV put the enterprise on a new footing, founding a harbour at Newhaven and a dockyard at the Pools of Airth. He acquired a total of 38 ships including the ''

There were various attempts to create royal naval forces in the 15th century. James IV put the enterprise on a new footing, founding a harbour at Newhaven and a dockyard at the Pools of Airth. He acquired a total of 38 ships including the ''

Before the

Before the  In the early 17th century, relatively large numbers of Scots took service in foreign armies involved in the

In the early 17th century, relatively large numbers of Scots took service in foreign armies involved in the

online

* Brown, Keith M. ''Kingdom Or Province?: Scotland and the Regal Union 1603–1715'' (Macmillan International Higher Education, 1992). * Lang, Andrew. ''The History of Scotland – Volume 4: From the massacre of Glencoe to the end of Jacobitism'' (Jazzybee Verlag, 2016). * Macinnes, Allan I. ''A history of Scotland'' (Bloomsbury, 2018). * Moffat, Alistair. ''The Faded Map: The Lost Kingdoms of Scotland'' (Birlinn, 2011). * Oram, Richard. "'The worst disaster suffered by the people of Scotland in recorded history': climate change, dearth and pathogens in the long 14th century." ''Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland'' Vol. 144. (2015)

online

* Reid, Norman. "The kingless kingdom: the Scottish guardianships of 1286–1306." ''Scottish Historical Review'' 61.172 (1982): 105–129. * Taylor, Alice. ''The shape of the state in medieval Scotland, 1124–1290'' (Oxford University Press, 2016). * Whatley, Christopher A. "The Union of 1707." in ''Modern Scottish History: Volume 1: The Transformation of Scotland, 1707–1850'' (2022). * Wormald, Jenny, ed. ''Scotland: a history'' (Oxford University Press, 2011). {{DEFAULTSORT:Scotland, Kingdom Of 1707 disestablishments in Scotland Scottish monarchy States and territories established in the 840s States and territories disestablished in 1707 States and territories disestablished in 1654 States and territories established in 1660

sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

in northwest Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, sharing a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, Scotland engaged in intermittent conflict with England, most prominently the Wars of Scottish Independence, which saw the Scots assert their independence from the English. Following the annexation of the Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

and the Northern Isles

The Northern Isles (; ; ) are a chain (or archipelago) of Island, islands of Scotland, located off the north coast of the Scottish mainland. The climate is cool and temperate and highly influenced by the surrounding seas. There are two main is ...

from Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

in 1266 and 1472 respectively, and the capture of Berwick by England in 1482, the territory of the Kingdom of Scotland corresponded to that of modern-day Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, bounded by the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

to the east, the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

to the southwest.

In 1603, James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

became King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

, joining Scotland with England in a personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

. In 1707, during the reign of Queen Anne, the two kingdoms were united to form the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

under the terms of the Acts of Union. The Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

was the most important element of Scotland's government. The Scottish monarchy in the Middle Ages was a largely itinerant institution, before Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

developed as a capital city

A capital city, or just capital, is the municipality holding primary status in a country, state (polity), state, province, department (administrative division), department, or other administrative division, subnational division, usually as its ...

in the second half of the 15th century. The Crown remained at the centre of political life and in the 16th century emerged as a major centre of display and artistic patronage, until it was effectively dissolved with the 1603 Union of Crowns. The Scottish Crown adopted the conventional offices of western European monarchical states of the time and developed a Privy Council and great offices of state. Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

also emerged as a major legal institution, gaining an oversight of taxation and policy, but was never as central to the national life. In the early period, the kings of the Scots depended on the great lords—the mormaer

In early medieval Scotland, a mormaer was the Gaelic name for a regional or provincial ruler, theoretically second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a '' Toísech'' (chieftain). Mormaers were equivalent to English earls or Continenta ...

s and toísechs—but from the reign of David I, sheriffdom

A sheriffdom is a judicial district in Scotland, led by a sheriff principal. Since 1 January 1975, there have been six sheriffdoms. Each sheriffdom is divided into a series of sheriff court districts, and each sheriff court is presided over by a r ...

s were introduced, which allowed more direct control and gradually limited the power of the major lordships.

In the 17th century, the creation of Justices of Peace and Commissioners of Supply

Commissioners of Supply were local administrative bodies in Scotland from 1667 to 1930. Originally established in each sheriffdom to collect tax, they later took on much of the responsibility for the local government of the counties of Scotland. ...

helped to increase the effectiveness of local government. The continued existence of courts baron and the introduction of kirk session

A session (from the Latin word ''sessio'', which means "to sit", as in sitting to deliberate or talk about something; sometimes called ''consistory'' or ''church board'') is a body of elected elders governing a particular church within presbyte ...

s helped consolidate the power of local laird

Laird () is a Scottish word for minor lord (or landlord) and is a designation that applies to an owner of a large, long-established Scotland, Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a Baronage of ...

s. Scots law

Scots law () is the List of country legal systems, legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing Civil law (legal system), civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different histori ...

developed in the Middle Ages and was reformed and codified in the 16th and 17th centuries. Under James IV the legal functions of the council were rationalised, with Court of Session

The Court of Session is the highest national court of Scotland in relation to Civil law (common law), civil cases. The court was established in 1532 to take on the judicial functions of the royal council. Its jurisdiction overlapped with othe ...

meeting daily in Edinburgh. In 1532, the College of Justice

The College of Justice () includes the Supreme Courts of Scotland, and its associated bodies. The constituent bodies of the national supreme courts are the Court of Session, the High Court of Justiciary, the Office of the Accountant of Court, ...

was founded, leading to the training and professionalisation of lawyers. David I is the first Scottish king known to have produced his own coinage. After the union of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603, the Pound Scots was reformed to closely match sterling coin. The Bank of Scotland

The Bank of Scotland plc (Scottish Gaelic: ''Banca na h-Alba'') is a commercial bank, commercial and clearing (finance), clearing bank based in Edinburgh, Scotland, and is part of the Lloyds Banking Group. The bank was established by the Par ...

issued pound notes from 1704. Scottish currency was abolished by the Acts of Union 1707; however, Scotland has retained unique banknotes to the present day.

Geographically, Scotland is divided between the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland, and the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act o ...

and the Lowlands. The Highlands had a relatively short growing season, which was even shorter during the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Mat ...

. Scotland's population at the start of the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

was about 1 million; by the end of the plague, it was only half a million. It expanded in the first half of the 16th century, reaching roughly 1.2 million by the 1690s. Significant languages in the medieval kingdom included Gaelic, Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

, Norse and French; but by the early modern era Middle Scots

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 15th century, its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtual ...

had begun to dominate. Christianity was introduced into Scotland from the 6th century. In the Norman period the Scottish church underwent a series of changes that led to new monastic orders and organisation. During the 16th century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

that created a predominately Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

national kirk. There were a series of religious controversies that resulted in divisions and persecutions. The Scottish Crown developed naval forces at various points in its history, but often relied on privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s and fought a '' guerre de course''. Land forces centred around the large common army, but adopted European innovations from the 16th century; and many Scots took service as mercenaries and as soldiers for the English Crown.

History

Origins: 400–943

From the 5th century on, north Britain was divided into a series of petty kingdoms. Of these, the four most important were those of thePicts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

in the north-east, the Scots of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

in the west, the Britons of Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Welsh language, Welsh; in Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic, meaning 'strath

in the south-west and the Anglian kingdom of alley

An alley or alleyway is a narrow lane, footpath, path, or passageway, often reserved for pedestrians, which usually runs between, behind, or within buildings in towns and cities. It is also a rear access or service road (back lane), or a path, w ...

of the River Clyde') was one of nine former Local government in Scotland, local government Regions and districts of Scotland, regions of Scotland cre ...Bernicia

Bernicia () was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was approximately equivalent to the modern English cou ...

(which united with Deira

Deira ( ; Old Welsh/ or ; or ) was an area of Post-Roman Britain, and a later Anglian kingdom.

Etymology

The name of the kingdom is of Brythonic origin, and is derived from the Proto-Celtic , meaning 'oak' ( in modern Welsh), in which case ...

to form Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

in 653) in the south-east, stretching into modern northern England.

In 793, ferocious Viking raids began on monasteries such as those at Iona and Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parishes in England, civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th centu ...

, creating fear and confusion across the kingdoms of north Britain. Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

, Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

and the Western Isles

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islands form part ...

eventually fell to the Norsemen. In a decisive battle in 839, the king of the Picts, Uuen, and the king of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

, Áed, were killed by Vikings. This led to a period of instability, which culminated in the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) as "king of the Picts" in the 840s (traditionally dated to 843),. and brought to power the House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpinid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from Constantine II (Causantín mac Áeda) ...

.

Under the House of Alpin, there was a long-term process of Gaelicisation

Gaelicisation, or Gaelicization, is the act or process of making something Gaels, Gaelic or gaining characteristics of the ''Gaels'', a sub-branch of Celticisation. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group, traditionally viewed as having spread fro ...

of the Pictish kingdoms, which adopted Gaelic language and customs. There was also a merger of the Gaelic (Scots) and Pictish kingdoms, although historians debate whether it was a Pictish takeover of Dál Riata, or vice-versa. When he died as king of the combined kingdom in 900, one of Kenneth's successors, Domnall II (Donald II), was the first man to be called ''rí Alban'' (King of Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English-language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingd ...

). The Latin term Scotia would increasingly be used to describe the heartland of these kings, north of the River Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic name for the ...

, and eventually the entire area controlled by its kings would be referred to, in English, as Scotland.. The long reign (900–942/3) of Donald's successor Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba/Scotland, and he was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church.

Expansion: 943–1513

Máel Coluim I (Malcolm I) ( 943–954) is believed to have annexed theKingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (, "valley of the River Clyde, Clyde"), also known as Cumbria, was a Celtic Britons, Brittonic kingdom in northern Britain during the Scotland in the Middle Ages, Middle Ages. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland an ...

, over which the kings of Alba had probably exercised some authority since the later 9th century. His successor, Indulf the Aggressor, was described as the King of Strathclyde before inheriting the throne of Alba; he is credited with later annexing parts of Lothian, including Edinburgh, from the Kingdom of Northumbria. The reign of David I has been characterised as a "Davidian Revolution

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregoria ...

",. in which he introduced a system of feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

land tenure, established the first royal burgh

A royal burgh ( ) was a type of Scottish burgh which had been founded by, or subsequently granted, a royal charter. Although abolished by law in 1975, the term is still used by many former royal burghs.

Most royal burghs were either created by ...

s in Scotland and the first recorded Scottish coinage, and continued a process of religious and legal reforms..

Until the 13th century, the border with England was very fluid, with Northumbria being annexed to Scotland by David I, but lost under his grandson and successor Malcolm IV

Malcolm IV (; ), nicknamed Virgo, "the Maiden" (between 23 April and 24 May 1141 – 9 December 1165) was King of Scotland from 1153 until his death. He was the eldest son of Henry of Scotland, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, Henry, Earl of Huntingdon ...

in 1157. The Treaty of York (1237) fixed the boundaries with England close to the modern border.

By the reign of Alexander III, the Scots had annexed the remainder of the Norwegian-held western seaboard after the stalemate of the Battle of Largs

The Battle of Largs (2 October 1263) was a battle between the kingdoms of Kingdom of Norway (872–1397), Norway and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, on the Firth of Clyde near Largs, Scotland. The conflict formed part of the Scottish–Norwegian ...

and the Treaty of Perth in 1266.. The Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

fell under English control, from Norwegian, in the 14th century, despite several attempts to seize it for Scotland.

The English briefly occupied most of Scotland, under Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

. Under Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, the English backed Edward Balliol, son of King John Balliol, in an attempt to gain his father's throne and restore the lands of the Scottish lords dispossessed by Robert I Robert I may refer to:

* Robert I, Duke of Neustria (697–748)

*Robert I of France (866–923), King of France, 922–923, rebelled against Charles the Simple

* Rollo, Duke of Normandy (c. 846 – c. 930; reigned 911–927)

* Robert I Archbishop o ...

and his successors in the 14th century in the Wars of Independence (1296–1357). The king of France attempted to thwart the exercise, under the terms of what became known as the Auld Alliance, which provided for mutual aid against the English.

In the 15th and early 16th centuries, under the Stewart Dynasty, despite a turbulent political history, the Crown gained greater political control at the expense of independent lords and regained most of its lost territory to around the modern borders of the country.. The dowry of the Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

and Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

Islands, by the Norwegian crown, in 1468 was the last great land acquisition for the kingdom. In 1482 the border fortress of Berwick—the largest port in medieval Scotland—fell to the English once again; this was the last time it changed hands. The Auld Alliance with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden Field in 1513 and the death of the King James IV. A long period of political instability followed.

Consolidation: 1513–1690

In the 16th century, under

In the 16th century, under James V of Scotland

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

and Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, the Crown and court took on many of the attributes of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

and New Monarchy

The New Monarchs is a concept developed by European Historian, historians during the first half of the 20th century to characterize 15th-century European rulers who unified their respective nations, creating stable and centralized governments. Th ...

, despite long royal minorities

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

, civil wars and interventions by the English and French. In the mid-16th century, the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Fr ...

was strongly influenced by Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

, leading to widespread iconoclasm

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

and the introduction of a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

system of organisation and discipline that would have a major impact on Scottish life.

In the late 16th century, James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

emerged as a major intellectual figure with considerable authority over the kingdom. In 1603, he inherited the thrones of England and Ireland, creating a Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single ...

that left the three states with their separate identities and institutions. He also moved the centre of royal patronage and power to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

.

When James' son Charles I attempted to impose elements of the English religious settlement on Scotland, the result was the Bishops' Wars

The Bishops' Wars were two separate conflicts fought in 1639 and 1640 between Scotland and England, with Scottish Royalists allied to England. They were the first of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which also include the First and Second En ...

(1637–1640), which ended in defeat for the king and a virtually independent Presbyterian Covenanter

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son C ...

state in Scotland.. It also helped precipitate the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities in a personal union un ...

, during which the Scots carried out major military interventions.

After Charles I's defeat, the Scots backed the king in the Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February and August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639–1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 164 ...

; after his execution, they proclaimed his son Charles II king, resulting in the Anglo-Scottish War of 1650–1652 against the emerging republican regime of Parliamentarians in England led by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

. The results were a series of defeats and the short-lived incorporation of Scotland into the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland (1653–1660).

After the 1660 restoration of the monarchy, Scotland regained its separate status and institutions, while the centre of political power remained in London.. After the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

of 1688–1689, in which James VII was deposed by his daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange in England, Scotland accepted them under the Claim of Right Act 1689

The Claim of Right (c. 28) () is an act passed by the Convention of the Estates, a sister body to the Parliament of Scotland (or Three Estates), in April 1689. It is one of the key documents of United Kingdom constitutional law and Scottish ...

, but the deposed main hereditary line of the Stuarts became a focus for political discontent known as Jacobitism

Jacobitism was a political ideology advocating the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British throne. When James II of England chose exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, ...

, leading to a series of invasions and rebellions mainly focused on the Scottish Highlands.

Treaty of Union: 1690–1707

After severe economic dislocation in the 1690s, there were moves that led to political union with England as theKingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

, which came into force on 1 May 1707. The English and Scottish parliaments were replaced by a combined Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union 1707, Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a ...

, which sat in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

and largely continued English traditions without interruption. Forty-five Scots were added to the 513 members of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

and 16 Scots to the 190 members of the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

. It was also a full economic union, replacing the Scottish systems of currency, taxation and laws regulating trade.

Government

The unified kingdom of Alba retained some of the ritual aspects of Pictish and Scottish kingship. These can be seen in the elaborate ritual coronation at the Stone of Scone at Scone Abbey.. While the Scottish monarchy in the Middle Ages was a largely itinerant institution,Scone

A scone ( or ) is a traditional British and Irish baked good, popular in the United Kingdom and Ireland. It is usually made of either wheat flour or oatmeal, with baking powder as a leavening agent, and baked on sheet pans. A scone is often ...

remained one of its most important locations, with royal castles at Stirling

Stirling (; ; ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Central Belt, central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town#Scotland, market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the roya ...

and Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

becoming significant in the later Middle Ages before Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

developed as a capital city in the second half of the 15th century.

The Crown remained the most important element of government, despite the many royal minorities

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

. In the late Middle Ages, it saw much of the aggrandisement associated with the New Monarchs elsewhere in Europe. Theories of constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

and resistance were articulated by Scots, particularly George Buchanan

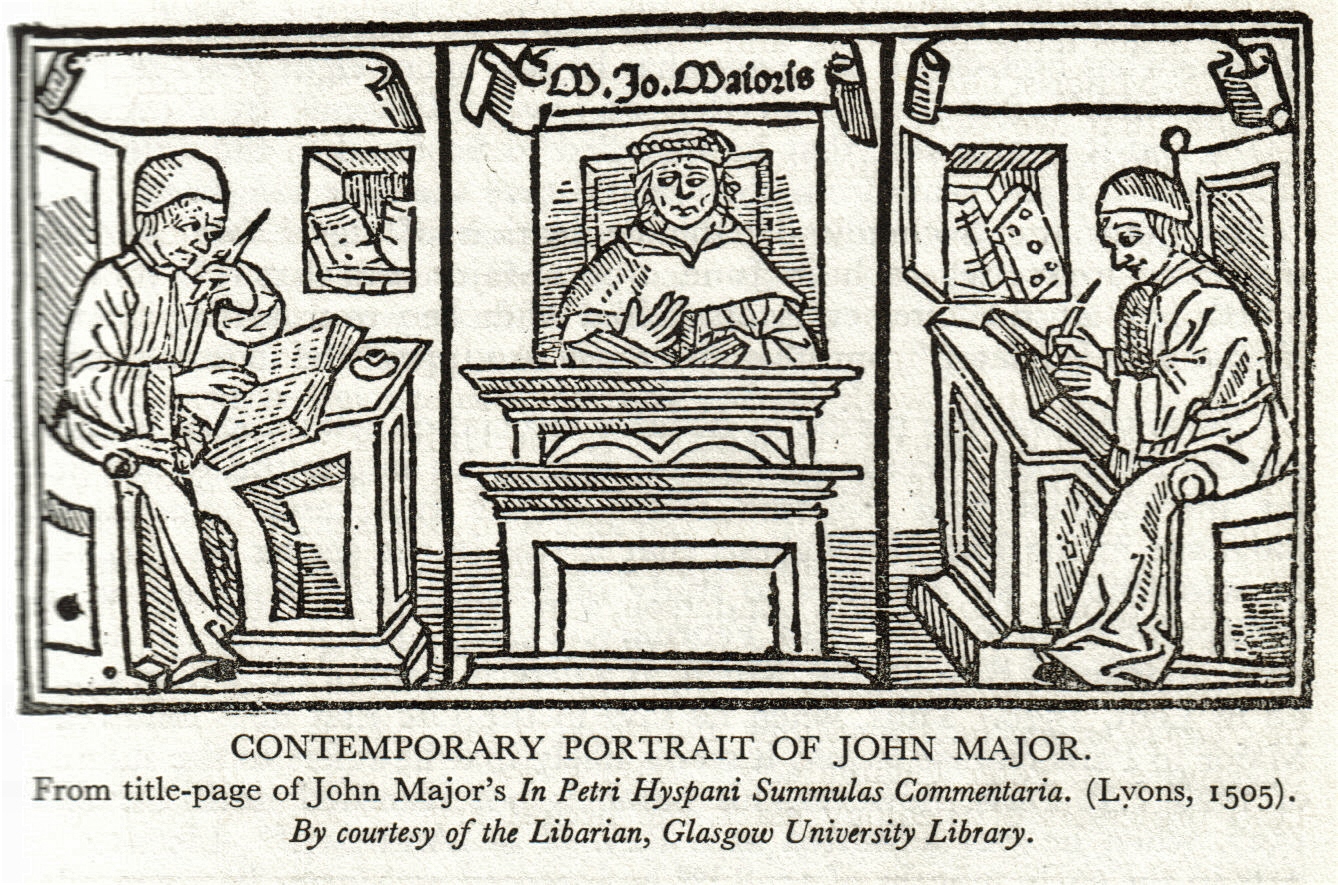

George Buchanan (; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth-century Scotland produced." His ideology of re ...

, in the 16th century, but James VI of Scotland advanced the theory of the divine right of kings, and these debates were restated in subsequent reigns and crises. The court remained at the centre of political life, and in the 16th century emerged as a major centre of display and artistic patronage, until it was effectively dissolved with the Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single ...

in 1603. The Privy Council of Scotland

The Privy Council of Scotland ( — 1 May 1708) was a body that advised the Scottish monarch. During its existence, the Privy Council of Scotland was essentially considered as the government of the Kingdom of Scotland, and was seen as the most ...

was the body that advised the Scottish monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British cons ...

. During its existence, the Privy Council of Scotland was essentially considered as the government of the Kingdom of Scotland, and was seen as the most important element of central government.

In the range of its functions the council was often more important than the Estates in the running the country. Its registers include a wide range of material on the political, administrative, economic and social affairs of the country. The council supervised the administration of the law, regulated trade and shipping, took emergency measures against the plague, granted licences to travel, administered oaths of allegiance, banished beggars and gypsies, dealt with witches

Witchcraft is the use of magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to ''Enc ...

, recusants, Covenanters

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son ...

and Jacobites and tackled the problem of lawlessness in the Highlands and the Borders.

The Scottish Crown adopted the conventional offices of western European courts, including High Steward, Chamberlain, Lord High Constable, Earl Marischal and Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

.. The King's Council emerged as a full-time body in the 15th century, increasingly dominated by laymen and critical to the administration of justice. The Privy Council, which developed in the mid-16th century, and the great offices of state, including the chancellor, secretary and treasurer

A treasurer is a person responsible for the financial operations of a government, business, or other organization.

Government

The treasury of a country is the department responsible for the country's economy, finance and revenue. The treasure ...

, remained central to the administration of the government, even after the departure of the Stuart monarchs to rule in England from 1603. However, it was often sidelined and was abolished after the Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union refer to two acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, followed shortly thereafter by an equivalent act of the Parliament of England. They put into effect the international Treaty of Union agree ...

, with rule direct from London.

The

The Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

also emerged as a major legal institution, gaining an oversight of taxation and policy. By the end of the Middle Ages it was sitting almost every year, partly because of the frequent royal minorities and regencies of the period, which may have prevented it from being sidelined by the monarchy. In the early modern era, Parliament was also vital to the running of the country, providing laws and taxation, but it had fluctuating fortunes and was never as central to the national life as its counterpart in England.

In the early period, the kings of the Scots depended on the great lords of the mormaer

In early medieval Scotland, a mormaer was the Gaelic name for a regional or provincial ruler, theoretically second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a '' Toísech'' (chieftain). Mormaers were equivalent to English earls or Continenta ...

s (later earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the Peerages in the United Kingdom, peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount. A feminine form of ''earl'' never developed; instead, ...

s) and toísechs (later thanes), but from the reign of David I, sheriffdom

A sheriffdom is a judicial district in Scotland, led by a sheriff principal. Since 1 January 1975, there have been six sheriffdoms. Each sheriffdom is divided into a series of sheriff court districts, and each sheriff court is presided over by a r ...

s were introduced, which allowed more direct control and gradually limited the power of the major lordships.. In the 17th century, the creation of justices of the peace and the Commissioner of Supply helped to increase the effectiveness of local government. The continued existence of courts baron and introduction of kirk sessions helped consolidate the power of local laird

Laird () is a Scottish word for minor lord (or landlord) and is a designation that applies to an owner of a large, long-established Scotland, Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a Baronage of ...

s.

Law

Scots law developed into a distinctive system in the Middle Ages and was reformed and codified in the 16th and 17th centuries. Knowledge of the nature of Scots law before the 11th century is largely speculative,. but it was probably a mixture of legal traditions representing the different cultures inhabiting the land at the time, including

Scots law developed into a distinctive system in the Middle Ages and was reformed and codified in the 16th and 17th centuries. Knowledge of the nature of Scots law before the 11th century is largely speculative,. but it was probably a mixture of legal traditions representing the different cultures inhabiting the land at the time, including Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

, Britonnic, Irish and Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

customs. The legal tract, the '' Leges inter Brettos et Scottos'', set out a system of compensation for injury and death based on ranks and the solidarity of kin groups. in . There were popular courts or '' comhdhails'', indicated by dozens of place names in eastern Scotland. In Scandinavian-held areas, Udal law

Udal law is a Norsemen, Norse-derived legal system, found in Shetland and Orkney in Scotland, and in Manx law in the Isle of Man. It is closely related to Odelsrett; both terms are from Proto-Germanic Odal (rune), *''Ōþalan'', meaning "herita ...

formed the basis of the legal system and it is known that the Hebrides were taxed using the Ounceland measure. Althings were open-air governmental assemblies that met in the presence of the '' Jarl'' and the meetings were open to virtually all "free men". At these sessions decisions were made, laws passed and complaints adjudicated.

The introduction of feudalism in the reign of David I of Scotland

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim (Scottish Gaelic, Modern Gaelic: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th century ruler and saint who was David I as Prince of the Cumbrians, Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 112 ...

would have a profound impact on the development of Scottish law, establishing feudal land tenure

Under the English feudal system several different forms of land tenure existed, each effectively a contract with differing rights and duties attached thereto. Such tenures could be either free-hold if they were hereditable or perpetual or non-fr ...

over many parts of the south and east that eventually spread northward. Sheriffs, originally appointed by the King as royal administrators and tax collectors, developed legal functions. Feudal lords also held courts to adjudicate disputes between their tenants.

By the 14th century, some of these feudal courts had developed into "petty kingdoms" where the King's courts did not have authority except for cases of treason. Burgh

A burgh ( ) is an Autonomy, autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots language, Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when David I of Scotland, King David I created ...

s also had their local laws dealing mostly with commercial and trade matters and may have become similar in function to sheriff's courts. Ecclesiastical court

In organized Christianity, an ecclesiastical court, also called court Christian or court spiritual, is any of certain non-adversarial courts conducted by church-approved officials having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. Histo ...

s had exclusive jurisdiction over matters such as marriage, contracts made on oath, inheritance and legitimacy. ''Judices'' were often royal officials who supervised baronial, abbatial and other lower-ranking "courts".. However, the main official of law in the post-Davidian Kingdom of the Scots was the Justiciar

Justiciar is the English form of the medieval Latin term or (meaning "judge" or "justice"). The Chief Justiciar was the king's chief minister, roughly equivalent to a modern Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

The Justiciar of Ireland was ...

who held courts and reported to the king personally. Normally, there were two Justiciarships, organised by linguistic boundaries: the Justiciar of Scotia and the Justiciar of Lothian, but sometimes Galloway

Galloway ( ; ; ) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the counties of Scotland, historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council areas of Scotland, council area of Dumfries and Gallow ...

also had its own Justiciar. Scottish common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

, the ''jus commune

or is Latin for "common law" in certain jurisdictions. It is often used by Civil law (legal system), civil law jurists to refer to those aspects of the civil law system's invariant legal principles, sometimes called "the law of the land" in Eng ...

'', began to take shape at the end of the period, assimilating Gaelic and Britonnic law with practices from Anglo-Norman England and the Continent.

There is some evidence that, during the period of English control over Scotland,

There is some evidence that, during the period of English control over Scotland, Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 1254 ...

attempted to abolish Scottish laws in opposition to English law

English law is the common law list of national legal systems, legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly English criminal law, criminal law and Civil law (common law), civil law, each branch having its own Courts of England and Wales, ...

as he had done in Wales. Under Robert I in 1318, a parliament at Scone enacted a code of law that drew upon older practices. It codified procedures for criminal trials and protections for vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

s from ejection from the land. From the 14th century, there are surviving examples of early Scottish legal literature, such as the '' Regiam Majestatem'' (on procedure at the royal courts) and the ''Quoniam Attachiamenta'' (on procedure at the barons court), which drew on both common and Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

.

Customary laws, such as the Law of Clan MacDuff, came under attack from the Stewart Dynasty which consequently extended the reach of Scots common law. From the reign of King James I a legal profession began to develop and the administration of criminal and civil justice was centralised. The growing activity of the parliament and the centralisation of administration in Scotland called for the better dissemination of Acts of the parliament to the courts and other enforcers of the law. In the late 15th century, unsuccessful attempts were made to form commissions of experts to codify, update or define Scots law. The general practice during this period, as evidenced from records of cases, seems to have been to defer to specific Scottish laws on a matter when available and to fill in any gaps with provisions from the common law embodied in Civil and Canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

, which had the advantage of being written.

Under James IV the legal functions of the council were rationalised, with a royal Court of Session

The Court of Session is the highest national court of Scotland in relation to Civil law (common law), civil cases. The court was established in 1532 to take on the judicial functions of the royal council. Its jurisdiction overlapped with othe ...

meeting daily in Edinburgh to deal with civil cases. In 1514, the office of justice-general was created for the Earl of Argyll

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount. A feminine form of ''earl'' never developed; instead, ''countess'' is used.

The titl ...

(and held by his family until 1628). In 1532, the Royal College of Justice

The College of Justice () includes the Supreme Courts of Scotland, and its associated bodies. The constituent bodies of the national supreme courts are the Court of Session, the High Court of Justiciary, the Office of the Accountant of Court, ...

was founded, leading to the training and professionalisation of an emerging group of career lawyers. The Court of Session placed increasing emphasis on its independence from influence, including from the king, and superior jurisdiction over local justice. Its judges were increasingly able to control entry to their own ranks. In 1672, the High Court of Justiciary

The High Court of Justiciary () is the supreme criminal court in Scotland. The High Court is both a trial court and a court of appeal. As a trial court, the High Court sits on circuit at Parliament House or in the adjacent former Sheriff C ...

was founded from the College of Justice as a supreme court of appeal.

Coinage

David I is the first Scottish king known to have produced his own coinage. There were soon mints at Edinburgh, Berwick and

David I is the first Scottish king known to have produced his own coinage. There were soon mints at Edinburgh, Berwick and Roxburgh

Roxburgh () is a civil parish and formerly a royal burgh, in the historic county of Roxburghshire in the Scottish Borders, Scotland. It was an important trading burgh in High Medieval to early modern Scotland. In the Middle Ages it had at lea ...

. Early Scottish coins were similar to English ones, but with the king's head in profile instead of full face. The number of coins struck was small and English coins probably remained more significant in this period.. The first gold coin was a noble (6s. 8d.) of David II. Under James I pennies and halfpennies of billon (an alloy of silver with a base metal) were introduced, and copper farthings appeared under James III.. In James V's reign the bawbee ( d) and half-bawbee were issued, and in Mary, Queen of Scot's reign a twopence piece, the hardhead, was issued to help "the common people buy bread, drink, flesh, and fish". The billon coinage was discontinued after 1603, but twopence pieces in copper continued to be issued until the Act of Union in 1707.

Early Scottish coins were virtually identical in silver content to English ones, but from onwards their silver content began to depreciate more rapidly than their English counterparts. Between 1300 and 1605, Scottish coins lost silver value at an average of 12 percent every decade, three times higher than the English rate. The Scottish penny became a base metal coin by and virtually disappeared as a separate coin from onwards.. In 1356, an English proclamation banned the lower quality Scottish coins from being circulated in England. After the union of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603, the Pound Scots was reformed to closely match

Early Scottish coins were virtually identical in silver content to English ones, but from onwards their silver content began to depreciate more rapidly than their English counterparts. Between 1300 and 1605, Scottish coins lost silver value at an average of 12 percent every decade, three times higher than the English rate. The Scottish penny became a base metal coin by and virtually disappeared as a separate coin from onwards.. In 1356, an English proclamation banned the lower quality Scottish coins from being circulated in England. After the union of the Scottish and English crowns in 1603, the Pound Scots was reformed to closely match coins of the pound sterling

The standard circulating coinage of the United Kingdom, British Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories is denominated in pennies and pounds sterling ( symbol "£", commercial GBP), and ranges in value from one penny sterling t ...

, with £12 Scots equal to £1 sterling. The Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

enacted proposals in 1695 to set up the Bank of Scotland

The Bank of Scotland plc (Scottish Gaelic: ''Banca na h-Alba'') is a commercial bank, commercial and clearing (finance), clearing bank based in Edinburgh, Scotland, and is part of the Lloyds Banking Group. The bank was established by the Par ...

. The bank issued pound notes from 1704, which had the face value of £12 Scots. Scottish currency was abolished after the 1707 Act of Unions, with Scottish coins in circulation being drawn in to be re-minted according to English standards.

Geography

At its borders in 1707, the Kingdom of Scotland was half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inlandloch

''Loch'' ( ) is a word meaning "lake" or "inlet, sea inlet" in Scottish Gaelic, Scottish and Irish Gaelic, subsequently borrowed into English. In Irish contexts, it often appears in the anglicized form "lough". A small loch is sometimes calle ...

s, it had roughly the same amount of coastline at . Scotland has over 790 offshore islands, most of which are to be found in four main groups: Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

, Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

, and the Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

, subdivided into the Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides ( ; ) is an archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, which experience a mild oceanic climate. The Inner Hebrides compri ...

and Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an Archipelago, island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islan ...

. Only a fifth of Scotland is less than 60 metres above sea level. The defining factor in the geography of Scotland is the distinction between the Highlands and Islands in the north and west and the Lowlands in the south and east. The highlands are further divided into the Northwest Highlands

The Northwest Highlands are located in the northern third of Scotland that is separated from the Grampian Mountains by the Great Glen (Glen More). The region comprises Wester Ross, Assynt, Sutherland and part of Caithness. The Caledonian Cana ...

and the Grampian Mountains

The Grampian Mountains () is one of the three major mountain ranges in Scotland, that together occupy about half of Scotland. The other two ranges are the Northwest Highlands and the Southern Uplands. The Grampian range extends northeast to so ...

by the fault line of the Great Glen. The Lowlands are divided into the fertile belt of the Central Lowlands

The Central Lowlands, sometimes called the Midland Valley or Central Valley, is a geologically defined area of relatively low-lying land in southern Scotland. It consists of a rift valley between the Highland Boundary Fault to the north and ...

and the higher terrain of the Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands () are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas (the others being the Central Lowlands and the Highlands). The term is used both to describe the geographical region and to col ...

, which included the Cheviot Hills, over which the border with England ran. The Central Lowland belt averages about in width and, because it contains most of the good quality agricultural land and has easier communications, could support most of the urbanisation and elements of conventional government. However, the Southern Uplands, and particularly the Highlands were economically less productive and much more difficult to govern.

Its east Atlantic position means that Scotland has very heavy rainfall: today about 700 mm per year in the east and over 1000 mm in the west. This encouraged the spread of blanket bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and musk ...

s, the acidity of which, combined with high level of wind and salt spray, made most of the islands treeless. The existence of hills, mountains, quicksands and marshes made internal communication and conquest extremely difficult and may have contributed to the fragmented nature of political power. The Uplands and Highlands had a relatively short growing season, in the extreme case of the upper Grampians an ice free season of four months or less and for much of the Highlands and Uplands of seven months or less. The early modern era also saw the impact of the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Mat ...

, with 1564 seeing thirty-three days of continual frost, where rivers and lochs froze, leading to a series of subsistence crises until the 1690s.

Demography

From the formation of the

From the formation of the Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba (; ) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the First War of Scotti ...

in the 10th century until before the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

arrived in 1349, estimates based on the amount of farmable land suggest that population may have grown from half a million to a million. Although there is no reliable documentation on the impact of the plague, there are many anecdotal references to abandoned land in the following decades. If the pattern followed that in England, then the population may have fallen to as low as half a million by the end of the 15th century.

Compared with the situation after the redistribution of population in the later Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resulted from Scottish Agricultural R ...

and the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, these numbers would have been relatively evenly spread over the kingdom, with roughly half living north of the River Tay

The River Tay (, ; probably from the conjectured Brythonic ''Tausa'', possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing' David Ross, ''Scottish Place-names'', p. 209. Birlinn Ltd., Edinburgh, 2001.) is the longest river in Sc ...

. Perhaps ten per cent of the population lived in one of many burgh

A burgh ( ) is an Autonomy, autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots language, Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when David I of Scotland, King David I created ...

s that grew up in the later medieval period, mainly in the east and south. They would have had a mean population of about 2000, but many would have been much smaller than 1000 and the largest, Edinburgh, probably had a population of over 10,000 by the end of the Medieval era.

Price inflation, which generally reflects growing demand for food, suggests that the population probably expanded in the first half of the 16th century, levelling off after the famine of 1595, as prices were relatively stable in the early 17th century. Calculations based on hearth tax

A hearth tax was a property tax in certain countries during the medieval and early modern period, levied on each hearth, thus by proxy on wealth. It was calculated based on the number of hearths, or fireplaces, within a municipal area and is con ...

returns for 1691 indicate a population of 1,234,575, but this figure may have been seriously affected by the subsequent famines of the late 1690s. By 1750, with its suburbs, Edinburgh reached 57,000. The only other towns above 10,000 by the same time were Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

with 32,000, Aberdeen

Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh ...

with around 16,000 and Dundee

Dundee (; ; or , ) is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city in Scotland. The mid-year population estimate for the locality was . It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firt ...

with 12,000.

Language

Pictish language

Pictish is an extinct Brittonic Celtic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from late antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geo ...

in the north and Cumbric languages in the south were overlaid and replaced by Gaelic, Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

and later Norse in the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

. By the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

, the majority of people within Scotland spoke the Gaelic language, then simply called ''Scottish'', or in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, ''lingua Scotica''. In the Northern Isles the Norse language brought by Scandinavian occupiers and settlers evolved into the local Norn, which lingered until the end of the 18th century, and Norse may also have survived as a spoken language until the 16th century in the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an Archipelago, island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islan ...

. French, Flemish and particularly English became the main languages of Scottish burghs, most of which were located in the south and east, an area to which Anglian settlers had already brought a form of Old English. In the later part of the 12th century, the writer Adam of Dryburgh described lowland Lothian as "the Land of the English in the Kingdom of the Scots". At least from the accession of David I, Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court and was probably replaced by French, as evidenced by reports from contemporary chronicles, literature and translations of administrative documents into the French language.

In the Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

, Early Scots, then called English, became the dominant spoken language of the kingdom, aside from in the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland, and the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).